Head-vases

Highlighted Works of Art - 2005 Winter

|

|

Rome became the sole great power in the Mediterranean basin after the destruction of Carthage, its greatest enemy in the Western Mediterranean, in 146 BC. The Romans organized the area of present-day Tunisia, Libya and Eastern Algeria into the province Africa, which they controlled - with brief interruptions - up until 698 AD. On the conquered territories they founded new cities (Carthago Nova - New Carthage, Leptis Magna, Thuburbo Maius). Owing to their favourable geographical positions, these cities soon developed into significant centres, joined long-distance commerce, and maintained intensive relations with the entire Roman Empire. In the province of Africa large villa-estates were established, whose owners made great fortunes by producing oil, grain and grapes. The province experienced its golden age under the rule of the Severan dynasty (193-235 AD), which was of African origin. Forums, colonnaded roads, baths adorned with mosaics and marble, and theatres were built in addition to the richly decorated villas at the centres of the estates. Even though the decline of the Severan dynasty was followed by economic recession, about thirty years later the province, which was not directly affected by constant barbarian raids, regained its economic strength.

|

|

The first pottery workshops producing terra sigillata (Samian ware) appeared around 70 AD near the great estates situated in present-day Tunisia, in an environment boasting Punic traditions, with a culture and economy open towards both East and West. In antiquity this characteristic, glossy red-slip luxury ware, widespread in the entire Roman Empire, was referred to as Samian or Arretine (from today's Arezzo) after its two most important centres of production. Its re-discoverers in the Middle Ages held that the wares had descended from heaven, since they believed that no human hand could have ever created such beauty. The type produced in Africa had a lighter red slip than its Italian and Gaulish counterparts, and was therefore called light sigillata (terra sigillata chiara). In the beginning the workshops there imitated Italian and Gaulish types, but soon they found their own style and created their characteristic ceramic vessels, which were easily distinguishable from those produced in other Roman provinces. Whereas the products of European workshops were characterized by relief decoration from the mould, African potters preferred to adorn their wares with appliqué, stamped or grooved ornamentation, since this technique afforded them a far greater freedom in design. Unlike the Gaulish-Rheinish workshops, which gradually lost contact with the other branches of applied arts, the African workshops maintained a lively relationship with bone carving, toreutics and the production of textiles.

|

|

Thus, besides the mosaics and the stelai continuing Punic traditions, the African sigillata industry became one of the most characteristic and unique artistic expressions of the province. The clay-fields, water resources and forests providing fuel were in the possession of local landowners, and it was they who commissioned the potters and supervised the sale of the wares. Owing to the close connection between the pottery industry and agricultural production, African wares were exported to the Mediterranean, Britannia and Danube regions as well. Since this is the last Roman pottery type that exhibits intercontinental commercial relationships, it is also of great significance from the perspective of late Roman economic history.

Head-vases had been popular as early as Classical-Hellenistic times, but their production ceased at the beginning of the Roman imperial period. They caught on anew in the 2nd-3rd centuries AD in Asia Minor (especially Pergamon), Knidos and Athens, and later in North Africa. The North African variations were modelled after prototypes from Asia Minor, which often renders it difficult to distinguish between imported and locally produced pieces.

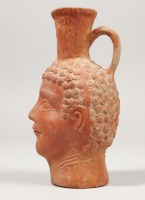

The wide-bodied wine-jug (lagynos) decorated with a grotesque male head showing Negroid features was probably produced in a Knidian workshop. Based on the hairstyle, it is datable to the period 150-220 AD. The 'rim' running around the body of the jug indicates the point where the two halves of the vessel were joined after their removal from the negative moulds.

The lower part of the body is decorated with the usual pattern of tongue-shaped leaves. On the upper part the otherwise characteristic hunting scene or Bacchian frieze is replaced with a wreath recalling the ornamentation of Pergamonian clay pilgrim-flasks. The lagynoi, which were in use at Dionysian festivals as well, were popular in both Asia Minor and North Africa.

The vessel forming a female head crowned with a wreath was also produced in Asia Minor (probably Knidos or Pergamon). As was customary with such vases, the face and the back of the head were cast in separate negative moulds. The two halves of the mould did not belong together: the front was simply joined to a stylistically matching back part. This is proved by the fact that the wreath does not continue on the back of the vase. The deep, sharp lines of the eyes, eyebrows and hair show further characteristic features of the techniques of production: after lifting the parts from the negative mould, fine details were fashioned freehand before firing. Based on the grooved design of the hair and other details, the vessel is datable to the late Antonine-Severan period (late 2nd-early 3rd century AD).

|

|

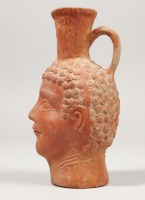

In Africa the workshops producing head-vases were closely connected to pottery workshops creating terra sigillata: in all probability some craftsmen who worked in both, overseen by the same owner. The vases decorated with a human head are associated with the cult of Bacchus (Dionysos, Liber Pater), who enjoyed great popularity in North Africa. Besides a number of tomb complexes that have so far been excavated, it is the often-schematic hairstyle that provides a key to the dating of the vessels. The pieces on display were made in the environs of Henchir es Srira, situated in the central region of present-day Tunisia, around 300 AD or somewhat later.

The vessel in the shape of a youth's head is made especially unique and valuable by the two-line stamp on its neck: Ex of

fi

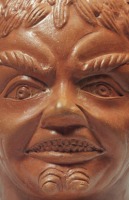

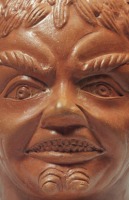

cina / Tachinatis, 'From the workshop of Tachinas'. Whereas Italian and Gaulish workshops producing terra sigillata always (András: very often) stamped their vessels, this practice was rather infrequent in Eastern and African workshops. The African head-vases could have been emblematic pieces of their workshops; in fact, it is assumed that their stamps may have served as advertisements for the owner or overseer of the respective workshop. The most striking vessel on display is the one that forms the grinning face of a satyr. The hair at the back of the head was modelled afterwards, like icing on a cake (en barbotine-technique). The head of the satyr is crowned with a diadem, which is decorated with rosettes on both sides. The deep grooves of the sculpted parts are in sharp contrast to the smooth surface of the body, and make the face strongly expressive. This piece was probably produced in the workshop of a master called Olithresis. Head-vases have so far come to light only from tombs. The vases modelled in the shape of a satyr, Bacchante, young man, drunken actor, or old woman can easily be associated with Bacchus, a god who enjoyed great popularity in North Africa. Perhaps the vessels not only expressed the comfort of wine in the face with the sorrow over death, but also, through the mysteries linked to the god, embodied hope for the deceased's rebirth.

Dénes Gabler - András Márton